The Musical Journey of Marlin Wallace

SPRINGFIELD, Mo.—Of the many things to know about Marlin Wallace, it all starts with a strong handshake. His meaningful grip was once seen on a union waterfront and along a cattle trail.Say hello to forgotten America.

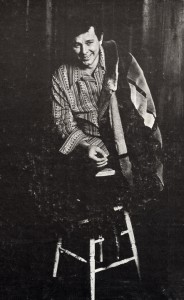

With his right hand the songwriter creates a vice-like covenant that flattens the fingers of a stranger. It is an old hand that has been hardened from 17 years of riding America’s rails as a hobo. Connections can be made in trains and in music and Wallace has spent his life chasing them down and taking notes.He is America’s most prolific songwriter.

He gives you a gotcha-smile as he shakes a hand.

Wallace was born in Springfield in 1937, and as a teenager played his father’s violin at Springfield area square dances. He has no memories of his birthfather who died at age 47. In 1953 Wallace got into a fight with his stepfather, who was a train operator. His stepfather’s leg was broken. Wallace was kicked out of the house. He spent time at a couple of relatives homes to live. There were no helping hands. Finally, Wallace was sent to a psychitraist. He spent three months undergoing electroshock treatment at a state hospital in Nevada, Mo.

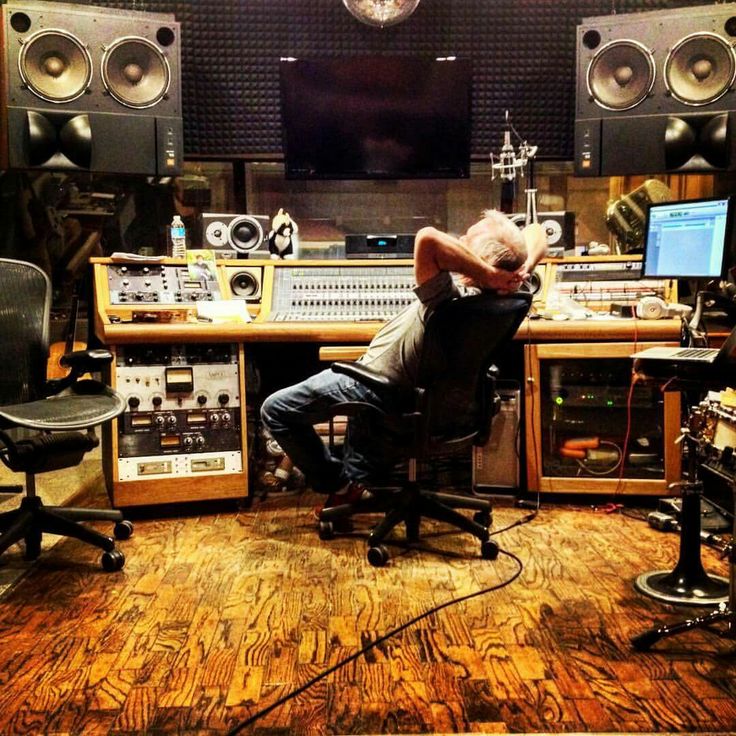

“It slowed me down but it didn’t help nothin’,” Wallace says during a February, 2014 interview at producer Lou Whitney’s studio in downtown Springfield. “One time there was a faulty machine that didn’t knock me out. It felt like a log chain went in your spine through your head. That’s how much pain I felt. They had us lined up taking that shock stuff.”

After he was discharged and a short stint in the Army, Wallace began riding the rails.He had to get away.

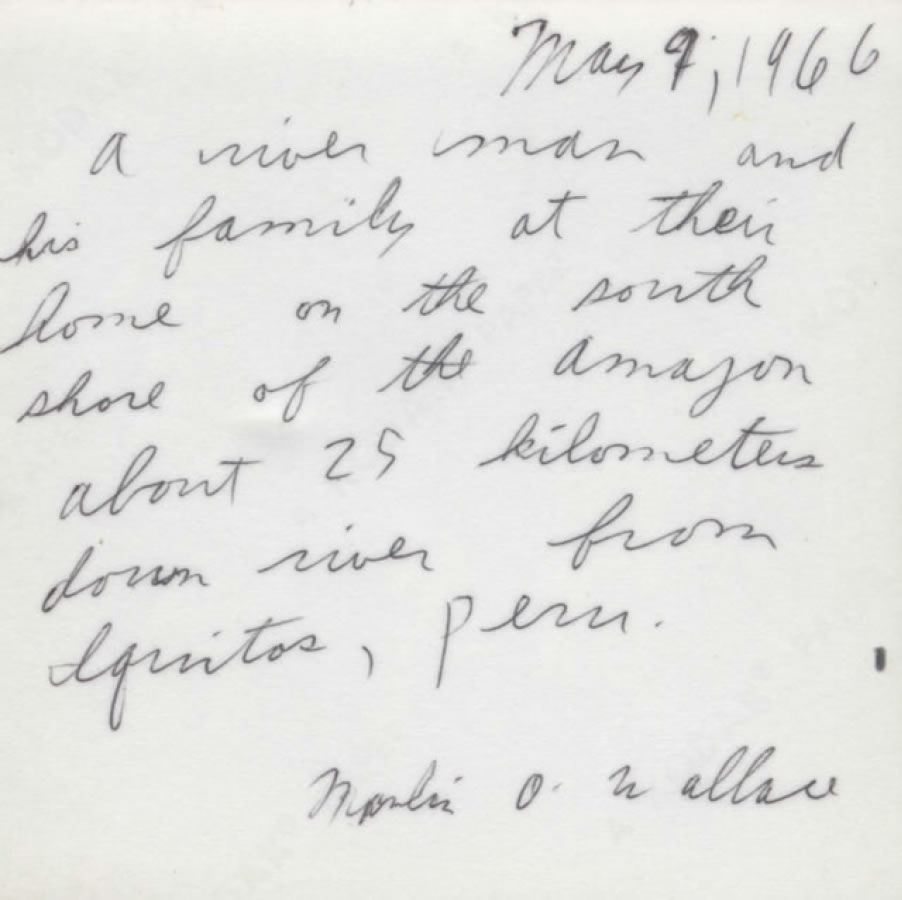

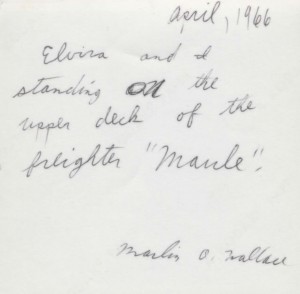

His most memorable journey was in the spring of 1966. Wallace jumped down to New Orleans, got on the Chilean freighter “Maule”which took him through the Panama Canal and down to Callalo, Peru. From there he grabbed a small airplane to Iquitos, Peru. He then floated 20 days alone in a small canoe on the Upper Amazon River.

He can prove it.

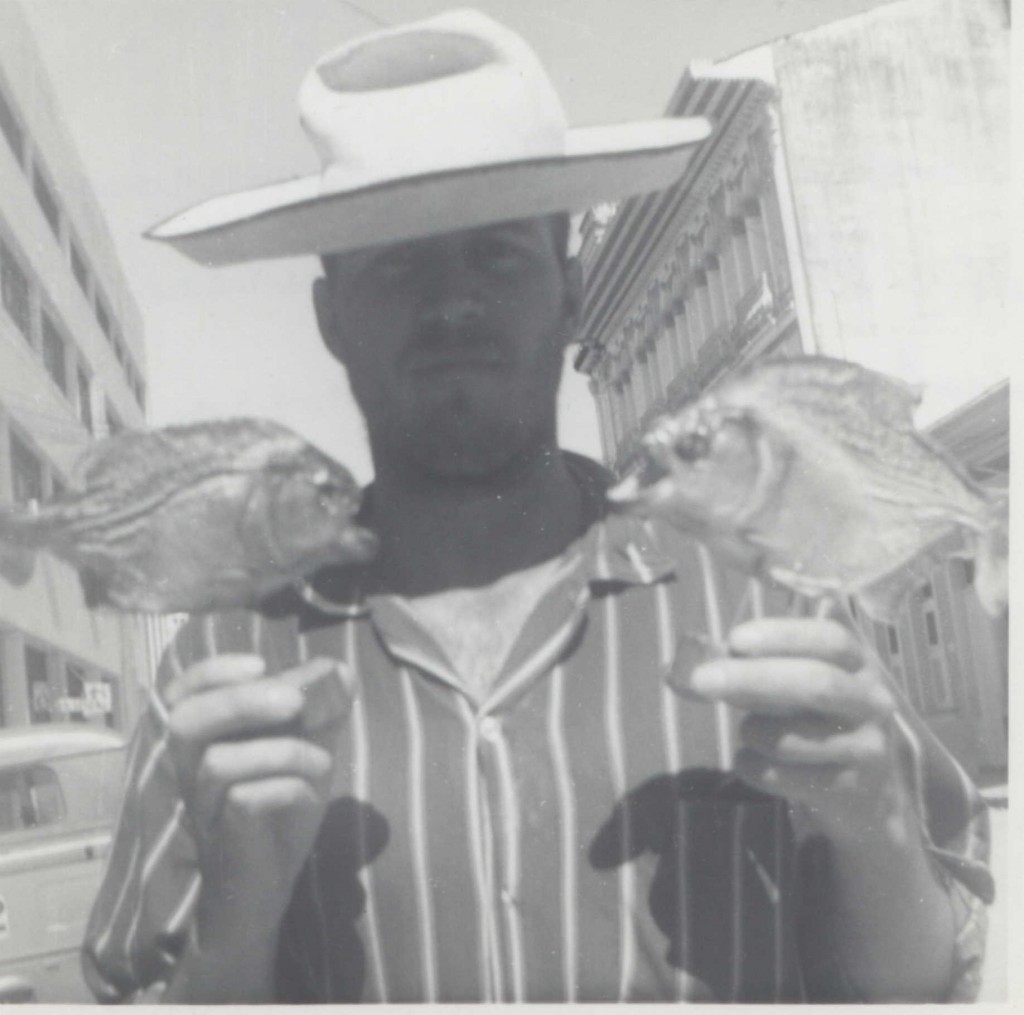

He took black and white pictures and faithfully sent postcards back to his mother in Springfield. There are several hundred postcards which documents a man’s journey into the unknown.

Wallace settled back in Springfield in 1972 and established The Corillions, which at different times is his singing group, recording label and home recording studio. He chose the name because of the Cordillera mountain range in the Philippines. Roughly translated, “Cordillera” is Spanish for “cord.”

Of course nothing has kept Wallace down.

He has copyrighted over 1,000 songs and in the late 1960s was briefly under contract with Dolly Parton’s “Parlowe” records which pressed his debut ’45 “Reno/”The Planet Mars.”

In the summer of 2004 Lou Whitney, the avatar of modern Springfield music, introduced former Morells keyboardist Dudley Brown to Wallace.

Brown immediately took Wallace under his wing.

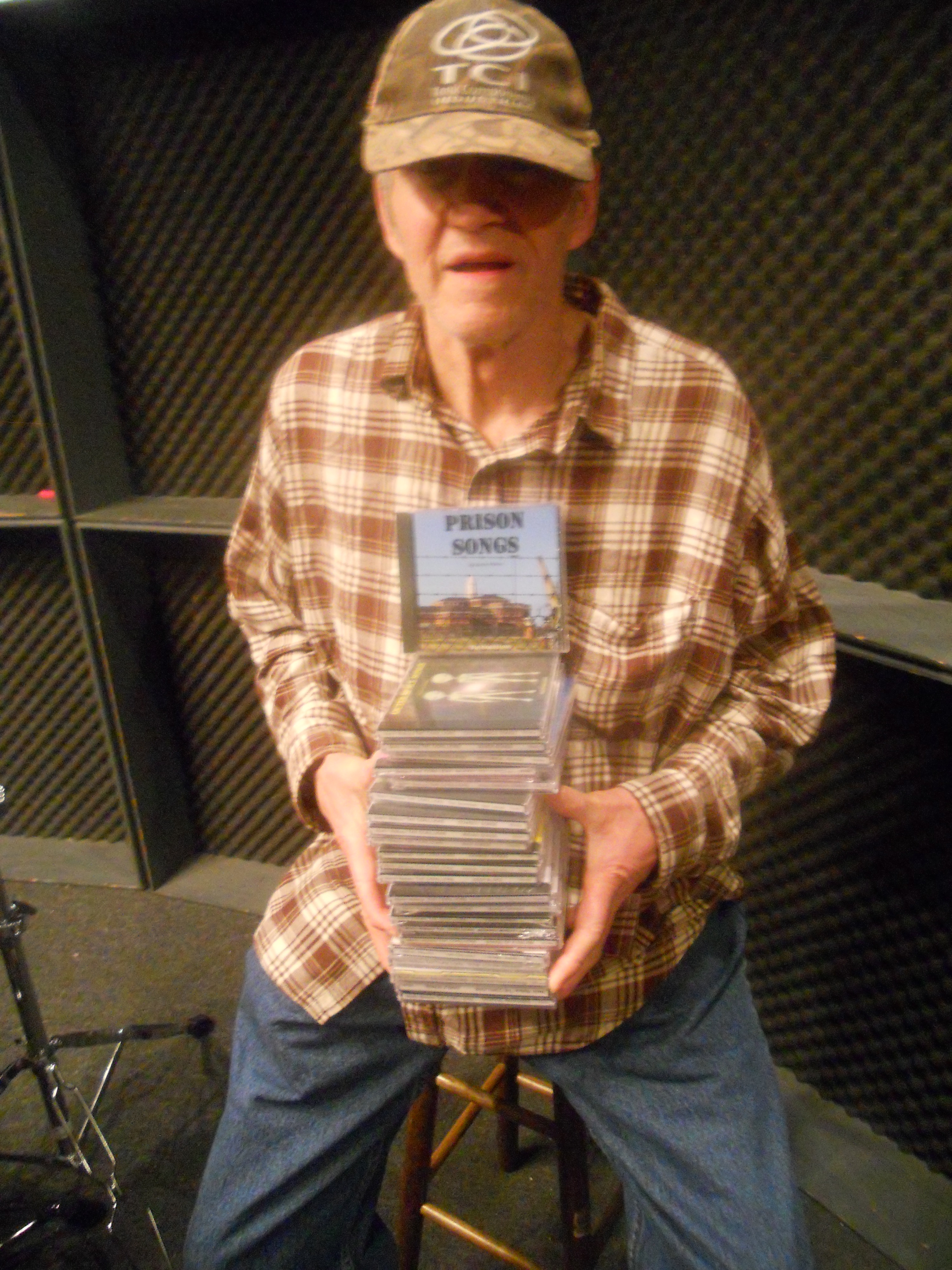

Since that first meeting, Wallace has recorded 50 full length CDS—more than 750 songs–in less than a decade.

Since that first meeting, Wallace has recorded 50 full length CDS—more than 750 songs–in less than a decade.The DIY CDs are themed: “Drinkin’ Songs,” Train Songs,” “Outer Space Songs” and “Prison Songs” (where the cover art is of the United States Medical Center for Federal Prisoners in Springfield where mobster John Gotti died in 2002.) All artwork is done by Springfield artists.Brown accompanies Wallace on keyboards and produces the wonderfully unfiltered music. The duo is currently working on “Country Songs, Vol. 15.” “In 16 months we’ve done 15 CDs,” Brown says. “There’s more to go. It’s a natural part of our lives.” Brown discovered several three ring notebooks filled with sheet music along with the historic collection of post cards all stored in Wallace’s backyard shed.

“You feel the positive energy of it all being creative,” Whitney says while sitting across from Wallace in his downtown Springfield studio. He grins and adds, “This is worker productivity.”

Wallace got some nice ink in the 2012 coffee table book “Enjoy The Experience (Homemade Records 1958-1992) [Siinecure Books, New York, Los Angeles] that spoke of what Wallace is mostly known for in “outsider art” circles: he believes Communists are zapping him with lasers. Even some of his current compact discs say, “FIGHT COMMUNISIM.” But to label Wallace as “outsider music” in the manner of the late Hasil Adkins is a grave disservice.

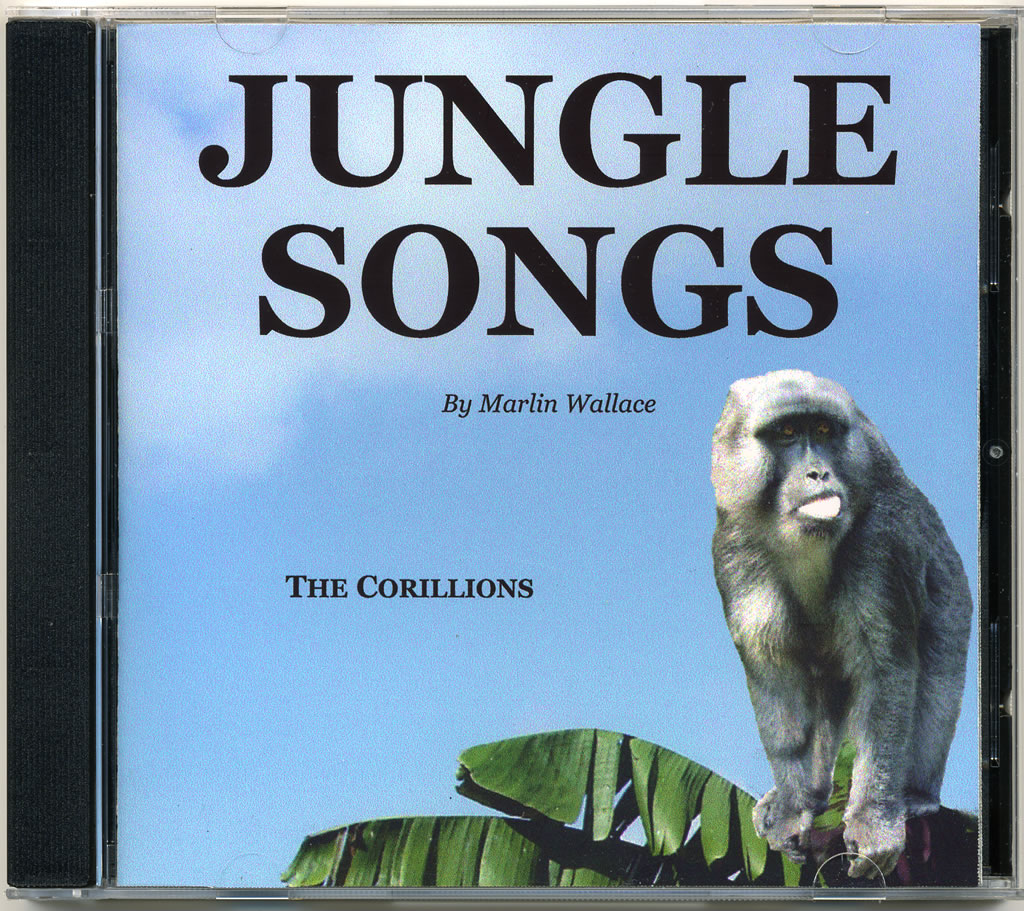

Wallace incorporates country, rockabilly, a smidgen of blues, rural gospel, and innocent pop (think NRBQ or Springfield’s own Skeletons.) I bought a copy of “Jungle Songs” and in an exotica background Wallace touches on primitive rap (“Jungle Jim”) and the rave-up rocker “The Jungle In Flight” where he imagines monkeys flying through the air.

Brown looks at a monkey on the cover of “Jungle Songs.”

He says, “This is actually a local macaque. The plumber that does work on Marlin’s place owns that guy. His name is Jo Jo. When I took his picture the plumber says, ‘If Jo Jo likes you he is going to come up and do his thing.’ He didn’t really say what his thing was. So I bent down and he was super nice, but my they smell.:

Jo Jo got real close to Brown and started sucking on this neck. “I was okay with it,” Brown says. “But then I’m doing research I learn that all macaques in captivity have this herpes B virus. And if you get one splatter in your eyeballs it can be fatal. Well, I had my glasses on, but I thought, ‘This is how I’m going to go out, getting herpes from a monkey’.”

All in the name for a Marlin Wallace CD cover.

A common thread in Wallace’s music is about longing and searching for sense of place, where Wallace draws on his hardscrabble childhood and his hobo years. “Memories of places have a bad side,” Wallace says. “You’d think a carefree hobo’s got no worries and there’s times like that. Other times I was depressed. I grew up with a lot of hate in me. I had had hate in me for years and it sticks in your gut. The Bible says ‘As a twig is bent so goes the tree.’ It’s nothing how Dudley grew up. He had a good home and a good upbringing. That didn’t happen for me. It’s like trying to outrun the devil. I’d be traveling but going a lot further than I needed to go.

“It was like something was driving me.”

On the galloping country “Ghost Train” vocalist Alton Davis sings in bass tones about how “the devil is the engineer/keeps his crew standing near….” “Heart Full of Rain” recalls the organic guitar strumming of J.J. Cale, who was from Tulsa, just down the road from Springfield.“Wanderin’ Soul” is another tune set rolling Tulsa-country rhythms. Wallace’s “wanderin’ soul” is being chased by Satan with train whistles blowing in the distance.Here is a snippet of “Wanderin’ Soul.”“Wanderin’ Soul” is the closest Wallace has come to being discovered by a mainstream audience. In 1975 late Arkansas vocalist Gary Atkinson sang “Wanderin’ Soul on the Corilllion label. In 2006 “Wanderin’ Soul” was re-released by the U.K. based Fat City Records in the compilation “45 Kings III.” That compilation wandered into the House Music scene where the gospel bass break that leads into the lyric “…Oh Satan, I hear you callin’” became a popular sample. The original ‘45 now sells for a minimum of $75 on eBay.

Wallace has never seen a penny of royalties.* * *

Marlin Wallace began recording music in 1977 at Nick Sibley’s Dungeon Studio in Springfield. The studio was known for nationwide commercial and jingle work. Wallace found other Ozark area vocalists to cover his songs. Wallace has sung on just two of his songs including “Wildcat Mabeline,” which ends with glass being broken and coffee cans being rattled.

“Marlin heard about me being a guy who had an ability to do this and that,” Whitney says. “He came out to see me at a bar on the south side. I was getting ready to go on a two month trip and couldn’t do it. I really, really wanted to do a song with him. Then I didn’t hear from Marlin for quite some time. We later talked songs and I think Marlin got miffed with me thinking I was one of ‘them.’ He went home and woodshedded.”

A few years later Wallace walked into Whitney’s studio.

He carried a large briefcase with 61 cassettes of his songs.

Whitney called his long time Morells-Skeletons drummer Lloyd Hicks (now with NRBQ). “We listened a lot of the songs,” Whitney says. “I wanted to get them down a little better so Marlin didn’t have to worry about recording. So Marlin came in on Tuesday mornings and we’d record on 10-inch reels. Every Tuesday morning. Marlin would sit there and play guitar and sing and I’d record. Marlin used local session guys at Dungeon. Lloyd played on some of them. But we never used a band.

“And we got them all.”

In 2000 Whitney had hired Brown to play in the Morells since original keyboard player Joe Terry was on the road with Dave Alvin. Brown was a member of the Morells from 2000-05. Whitney told Brown about Wallace.

In 2000 Whitney had hired Brown to play in the Morells since original keyboard player Joe Terry was on the road with Dave Alvin. Brown was a member of the Morells from 2000-05. Whitney told Brown about Wallace.Brown, who was born in 1960 in Springfield, Mo., earned Wallace’s trust by becoming the songwriter’s advocate in shady real estate dealings. Wallace’s home and home studio is on the northwest edge of the downtown area. “Marlin was being maneuvered out of his property,” Brown says. “So I just stepped in and bought Marlin’s property. It’s the house that Marlin lives in and a bulding next to it.”

Wallace lives alone.

He says he was married once, “for about 20 years.”

Wallace sighs and says, “I could have left my house. But I had nowhere to go.”

* * *

The singer-songwriter-hobo from Springfield, Mo. likes to wear his tattered baseball cap low as a teardrop over his eyes. His narrow face and wispy southern drawl recalls the late Levon Helm.

But one thing becomes clear: Wallace has unbending pride in his body of work, ranging from his heartfelt music to the postcards from the road which he mailed to his mother Theo Walls, a Springfield homemaker.

Brown gently picks up a large plastic binder of the postcards. Each card is organized in plastic sheets. “This is a one of a kind historical record starting on Sept. 11, 1955 and going all the way through 1972,” Brown says. “There’s some from South America. Others are just the (blank) two cent kind you could buy at the post office. Some of these stamps are awesome.”

Whitney says, “It’s chronicled. You can’t argue with it.”

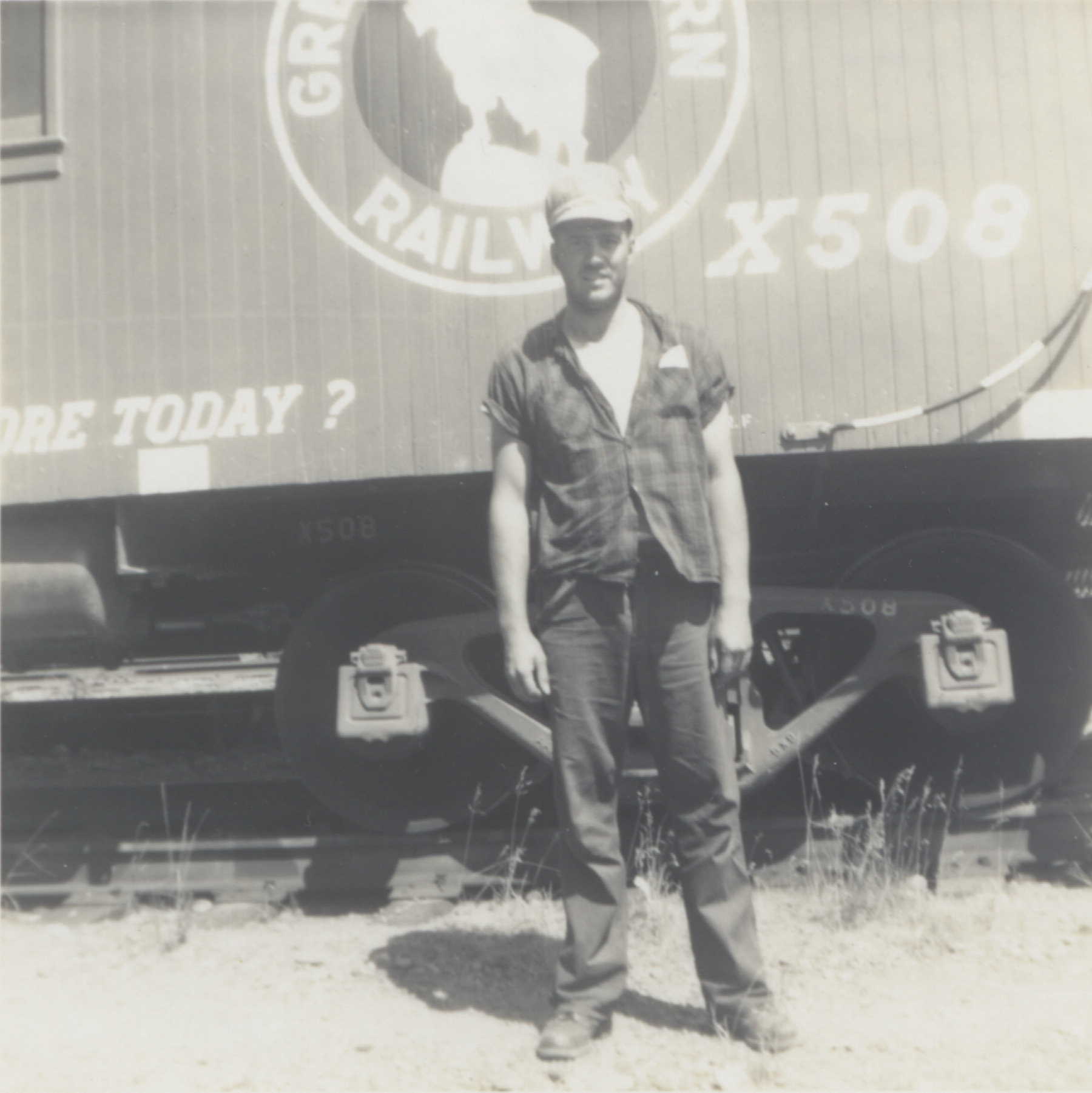

Wallace explains, “When I changed railroads I sent her the name of the railroad I was at. Each card has the initials of the railroad. I didn’t ride all the railroads, maybe 48. I rode the L&N (Louisville & Nashville), Florida East Coast.”

His first post card (9/11/55) is like a Tweet from today:

“I’m in Poplar Bluff, Missouri. We’re headed for Kentucky. So long.”

Springfield is a crossroads of railroads. The city was constructed on American optimism. Even the Worman House at the mega-popular Big Cedar Lodge in Branson, 30 miles south of Springfield, was built in 1921 as a rural retreat by Harry Worman, President of the Frisco Railroad.

Wallace can remember jumping his first train. He says, “In 1955 had a ‘42 Packard that broke down before I got into Pittsburgh. So I hitchiked into Pittsburgh and got freights going back to Springfield. I learned fast. When you run after it (the train) and grab the latch you get into a box car and swing your body up; they call that ‘catchin’ the train on the fly.’ Naturally, you try to get them when they are still. But jumping them is where I got the handshake.

“The boxcar grip.”

He also brought along a fiddle for his road trips. “I played in bars and passed the hat at bars in New Orleans,” he says. “I had a duffel bag with the fiddle in it and I would toss that on the train first. I was in Houston one time trying to catch the Rock Island. Boy when that came, I was running full steam and I swang that duffel bag around like it was a rag doll. You can die real quick.”

In 1966 Wallace ventured out on the mother of all hobo trips when he went to South America.

In 1966 Wallace ventured out on the mother of all hobo trips when he went to South America.“I wanted to get away from civilization,” he says. “I wanted a break from conformity. I wanted to get down to the jungle. I got a job washing dishes at the Monteleone Hotel in New Orleans waiting for this freighter to come in. I got a big double cabin to myself. I paid $150. I had a passport. I was on the ocean for three weeks. I got off at Lima. I was trying to get to the Amazon. I finally got to Iquitios (Peru), boy the river is wide there. I bought a small boat there and floated down to Leticia, Colombia (a major Amazon River port on the border of Peru) . About 360 miles. The river is pretty spooky especially when a big rain comes up. The first night I lost my flashlight.

“I decided to go to the bank of the river to take a leak. I tied up to a tree. Something was stinging all over my hand. I took the flashlight and saw my hand and arm was covered with fire ants from the tree. I dropped my flash light and got out of there as fast as I could. I went to the middle of the river. I had trouble swimming around that Amazon.”

But wait. There’s more.

Brown pulls out a fat, yellowed ledger. “In these sheets he documented the mileage he went on these trips,” Brown says. He then reads from the penciled notations, “South Dakota, June 9, 1961; Muskogee to Kansas City, 247 miles. K.C. to Omaha, 237 miles. Those are hot-shots, right? (No stops).” Wallace nods his head in agreement.

Brown continues, “Omaha to Sioux Falls, 177; Sioux Falls to Fort Dodge (Iowa) 197; Fort Dodge to Minneapolis 414! Minneapolis to Chicago 395, that’s a good haul too, Chicago to K.C. 414, K.C. to Springfield, Missouri 196.”

Wallace hears the numbers add up and says, “I’d come home and take out an atlas and look at the scale. I’d measure off so many miles by inch, 180 miles and so forth. Every time I made a big run I’d write it down.

“I’ve gone around the world four times, stretched out in one line.”

* * *

Marlin Wallace still churns out songs with the force of an old steam engine.

He works each song out on guitar and then puts it on a cassette. Moving to keyboard, he will write out sheet music with staff notation along with a detailed lyric sheet. He has not performed in public since his nascent teenage fiddling days around Springfield.

“I don’t write as much as I used to,” he admits. “It takes time to finish them. Some are quick, some are slow. Sometimes when I don’t finish them people steal the material before I finish the songs. It may take me 10 years to finish a song. I can name songs they stole from me by spying on me in my own home.”

For example, Wallace says he had “Who Let the Dogs Out” poached from him. And while the 1998 Baha Men hit (which in truth came from Trinidad & Tobago Carnival season) sounds like a Wallace title, there’s more than enough good Wallace material that hasn’t been “stolen.”

Brown watches over Wallace’s songs. He says, “We make a copy of the song and do the poor man’s copyright. Then Marlin brings over the cassette, song sheet and lyric of the songs he decides for us to work up. We bang them out on the piano and get it into the computer. We now have a huge reservoir of songs to pull from.”

Wallace is a modern day Woody Guthrie. Woody was considered a “Red.” Marlin is tormented by the Reds. And just like Guthrie, his considerable travels have informed his music. “The Amazon River influenced me quite a bit,” he said. “I drank water right out of the Amazon. I’m writing a book right now.

“But I’m waiting for something good to happen.”

Whitney listens with wide eyes and the open heart that has made him one of the most empathetic producers in America. Whitney leans over and says in firm tones, “Marlin, let me tell you. If you don’t do anything else in this whole world but write all the songs you did, you have done one bunch of good stuff. Period. It doesn’t seem like that when you inch along……”

Wallace tenderly nods his head and says, “I know it.”

Whitney continues, “…..But if you take a look at the things you have accomplished. The places you have been. The songs you have written and the interest you generated. You have accomplished quite a bit. Talking in generalities, songwriting is a young man’s game. You have to be young to think everything you do is great. As you get older you think, ‘That’s been said before.’ Marlin totally transcends that. Marlin sees material in things he knows about. He knows a lot about black widow spiders. He knows a lot about the animal kingdom. He knows a lot about history. And he writes about that stuff.

“If anybody paid attention they would see it is transformative.”

Wallace says the Communists are still harrassing him and this angle is where people get sidetracked off the music. “It’s still happening but not as bad as it was,” he explains. “In the ‘70s it was terrible. I was kept awake all night long. The Reds put radiation attacks on me. I figured it was from satellites. They were torturing me, trying to drive me insane. They could hit me right now. The probe feels like somebody tapped you with a finger. Then they hit you with the laser, a series of twitch attacks. They have to zero in on you first. I’d hold a piece of ceramic over me to stop the attacks.

“In fact the toe on my right foot is broke from one of those attacks. In 1972 they hit me on the head with a laser. It was like my head was exploding. I jumped out of bed and ran into a door.

“Psychological warfare.”

Just like the music business.

Communist-inspired laser attacks are one genre’ that Wallace has declined to address in an album. He reasons, “It wouldn’t be received very well to say you’re hit by lasers and tortured by reds. But I’ve written four songs about the reds like ‘Machine Guns And Machetes’ about the reds in Central America.” The track is from his “War Songs” CD that also includes “General MacArthur,” “Brave Men of Uncle Sam” and “Mekong.”

Whitney says, “Some people would read his liner notes, and Marlin and I have had this discussion, and form some kind of opinion right off the bat. A lot of people get more interested what he writes on the back of the album rather than listening to it. But if you have a chance to go deeper–you’re fortunate to have a chance to go deeper.”

The instrumental Wallace track “Judgment Day” is a work of beauty, flavored by tropical steel guitar. * I love this.

“I came back from South America and started writing those,” he says. “Somebody in Nashville started to mimic my material with the flat notes I had in there. They put out ‘Hawaii Five-O’ and all that. I came back and hit them in the head with ‘Theme From Corillions’. This isn’t ‘outsider’ music. Anybody who does anything different is ‘outside.’ It is misleading.”

Wallace grew up in the Pentecostal church but strayed as an adult. He includes scorching contemporary gospel in his repertoire such as the country-jubilee “I Will Follow The Lamb,” flavored with profound bass vocals. “You get this emotionalism in religion awfully easy,” Wallace says “Follow the Lamb’ is one of the first religious songs I wrote. It seemed real easy to write. But they tell you to pray away your troubles. I can’t go that route.”

Whitney laughs and says, “That’s like faith based toxic waste removal!”

Brown earned a Bachelor of Science in Computer Science from Missouri State University. He is Manager of Information Systems (MIS) for MD Publications, Inc. (Transmission Digest, etc.) He finances the CDs.

“Over the years it has added up to a lot of money,” Brown says. “It is hard to estimate what we’ve spent since 2004. We spent around $10,000 to produce the first 5 CDs. That included re-mastering of all the old vinyl recordings and then the CD production. We pressed up to 1,000 each. After that, since we hardly sold any CDs (vinyl was sold to hard core collectors) we would only press up to 50 of each release. We don’t have to book studio time. We recorded them at my home studio (in southeast Springfield.).

Wallace interrupts, “Before he came along I spent $20,000 out of my own pocket working hard labor jobs. I was a janitor at the Colonial Hotel in Springfield. I hung turkeys at Hudson’s Foods.”

Wallace worked at a now-defunct poultry processing plant in downtown Springfield. When a truck of turkeys were unloaded, a person was assigned to take the turkeys out of their cages and hang them by their feet one by one onto an overhead assembly line conveyor belt of live turkeys. The turkeys were then taken to the “kill room.” This job helped Wallace fund his DIY LPs.

In the early 1990s Brown was recruited by Skeletons-Morells guitarist Donnie Thompson to play bass and sing in The Park Central Squares (named after a park in downtown Springfield) along with drummer Katie Coffman of the Debs.

At age 17 Brown took piano lessons from Pete Schuelzky (Queen City Punks) who schooled him on the blues scales and improvising in the classic 1-4-5 chord pattern. Schuelzky also helped Brown deconstruct Miles Davis’s “All Blues” (from 1959’s “Kind of Blue”) which gave him the sensibilities to play in ensemble and eventually collaborate with Wallace. Brown counterpoints Wallace with appointed instrumentation that is playful and purposeful.

“Marlin’s music is organic,” Brown explains. “It’s not rootsy, it is kind of like folk. We start straight from his song sheets and his demos. We have so many songs we’ve been trying to get down for the past 10 years. Over a thousand. We just sit down and bang out the chords on the piano. While I’m playing the piano Marlin will sing a track to a metronome where in most cases we’ve got the vocal down and a chord structure. That’s the roots of it all. You can take that and go anywhere with it. We have a nice easy pace. We work Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and maybe an eight hour day on Saturday if we get in a groove–which is no more time than I would spend if I was playing in a band.”

Wallace adds, “We experiment with different things. We pick a marimba or an organ to back up a song, whatever brings a song in. Brown says, “With a computer you have a pallate of sounds to choose from. So you can pick what kind of flavor you want to add to the music.”

Just like any other artist and producer, Brown and Wallace endure creative tension.

“We’re quite a bit different in a lot of ways,” Wallace says. He looks at Brown and says, “He’s a meticilous clean freak. I’m an old hobo. He flies off the handle. I just let it slide it off.”

Brown says, “But I’ve gotten better. A lot of time when you’re doing songs you put all this effort into it and get it to a certain state and you don’t want to turn loose of it. But you know it’s not working. Marlin can spot that stuff miles down the road way before I can. I’ve learned over the years to trust his judgment. For one thing, it is just one song out of over 1,000 so ‘chill out.’ I am more like ‘get the drums done, get the bass done’ and get it up to the level where it starts working for the song. Marlin has the gift of knowning what not to do. And in a creative process, that overall taste is important.

“It is recognizing the flavor of something and knowing what the real song is.”

In early June, 2007 Brown and Wallace made a cordial eight hour drive from Springfield to Chicago to do a half-hour song-documentary on the 17-year-locust. His “The Seventeen Year Locust” tribute to the locust from his “Buggy” album is an infectious combination of New Orleans Second Line rhythms and Cajun dance music. In his documentary narration Wallace explains there are 15 broods of the locust (the Biblical name for cicadas) in North America and they only appear east of the Great Plains. “They have little fear of man or beast,” he says in the doc.

Like Wallace, the locust are a mystery.

“Seventeen is a recurring number for Marlin,” Brown adds. “Seventeen year locust, seventeen years on the rails.” Wallace recalls, “We got in the car with a camera and got to Chicago and couldn’t hear one cicada. I thought, ‘Where did these bugs go?’ So I said, ‘Let’s drive south.’.”

Brown and Wallace took I-55 along Old Route 66 before finding a park filled with chirping cicadas. “We had a birds-eye nest,” Wallace says gleefully. “We took pictures of the trees covered with them.”

Brown says, “They were landing on us.”

Wallace stops to reflect. He says, “One of my best memory places was in Muskogee, Oklahoma. I was six years old and living in this boarding house. There was a big empty lot next door. I’d get out there and climb those trees. I’d see other kids walking down the street but I didn’t want to be with them. I discovered three or four cicadas down there at this young age. That was one of the best times of my life.

“I just stayed alone in this world of nature.”

There is no rhyme or surface reason for Wallace’s prolific nature. “I’ll come up with the idea first,” he explains. “I’ll get to thinking about a certain subject. Say a warthog.”

Of all the things Wallace could reference, he references a warthog.

“I start thinking about the warts,” he says. “Then the whole hog will develop. Then I have a song ‘Warthog’. Lookin’ out of the eyes of an animal, you have to get on their level and write from their viewpoint.”

Bob Dylan isn’t this succinct.

“Give Me Your Love” is a scorching blues track Wallace recorded in the late 1970s with Maurice Rock, a black singer from Springfield. “One Good Soul” was written by Wallace reflecting on his hobo days. “I was driven by these forces to ride the rails,” he says.

Back in her space age beehive hair days, Dolly Parton signed Wallace to her Owepar Publishing Company she had started with Porter Wagoner. The late Frank Dycus (“He Can’t Fill My Shoes” for Jerry Lee Lewis and “Is Forever Longer Than Always” for Dolly and Porter was a Owepar staff writer. Whitney says, “Back in the late ‘60s they took two songs of mine. I was writing songs and pitching them in Nashville. One was a country recitation song I wanted Porter to get. It was called ‘World’s Biggest Clown.’ They picked up a tune of Marlin’s too. Marlin had a bad experience. I had no experience.”

Wallace still has his contract, signed by Parton in cursive with a pair of breasts.

Wallace met Parton in her 17th Avenue South office on Music Row. “I played some tapes of songs,” he says. “She (accidentally) broke the tape of the one called ‘Mekong’ (a dark folk ballad sung by Jim Grandstaff) while she played it. On Feb. 13, 1969 Parton signed a contract to purchase the rights of Wallace’s “The Planet Mars.”

Trust is imperative whenever people make music together.

“Until I ran into Lou and Dudley I was always given a hard time by people,” Wallace says in measured tones. “It’s a bad story. I room full of staff writers steal people’s ideas. I never got anywhere. I’m not trying to promote myself as a singer as much as my material. I’m a non-conformist and forced into a corner by myself. I have to occupy my time. But as long as I’m kicking, I’ll keep kicking them out.”

Dudley Brown has spent more than $10,000 and invested countless hours in his efforts to share the considerable music of Marlin Wallace with the rest of the world.

He, too, is a hobo with a strong helping hand.

Why?

Brown considers the question for a few moments. He finally answers, “It is is a great endeavor. When I met Marlin I was interested in the ‘45s and how neat ‘Wanderin’ Soul’ was and then how neat the albums were. I was blown away trying to figure it all out. Somewhere along the line your realize this guy has written thousands of songs. Thousands. There’s only a handful of people on the planet that have ever done anything like this. And there’s only one Marlin Wallace. No one has done what he’s done. It is all so massive. The post cards, the maps, the music.”

Whitney adds, “If you sit down and visit with Marlin you either get it or you don’t. My visits with Marlin convinced me that one, he is productive. Two, his songs are good. And three, he’s an honest human being. I got the entire package but I couldn’t step up and do what Dudley’s done. And Dudley got it immediately without even meeting Marlin. The way Marlin meticulously put his cassettes together. If he’d do something and change his mind or made a mistake–in the unlikely event he made a mistake–he’d hit that record button, there would be a little kechang and it would carry on. That takes focus. Intuitiveness. And patience. It is wealth. You can’t go out and spend it, but it is wealth and it is valuable. It reflects effort, time and investment. It reflects belief and creativity.

“That’s wealth beyond what a lot of people ever dream of.”

Marlin Wallace looks around the room and asks, “How do we cash it in?”

To purchase the excellent music of Marlin Wallace please visit his Corillions website, intro by Lou Whitney.

Copyright, April, 2014 Dave Hoekstra

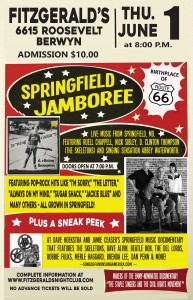

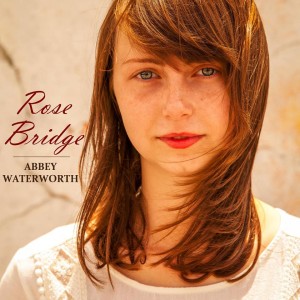

A few of our Springfield friends coming to FitzGerald’s in Berwyn (from far left Ruell Chappell, Nick Sibley on guitar, Abbey Waterworth, far right Donnie Thompson (and there’s the late great Bobby Lloyd Hicks on drums).

SPRINGFIELD, Mo.—The unadorned beauty of American regionalism can be heard in the songs of Abbey Waterworth. The 20-year-old musician is majoring in History and minoring in Museum Studies at Missouri State University (MSU) in Springfield. Her voice is as pure as mountain rain and filled with the promise of the morning sun. Waterworth is on the fast train to be to the Ozarks what a pop-country Dolly Parton is to Appalachia.

Waterworth came up with the idea to make her latest recording “Rose Bridge,” a sincere tribute to music that was created in the sticky flotsam and jetsam around Springfield.

Waterworth sings and plays banjo, Donnie Thompson (Skeletons, Morells, Steve Forbert) guests on lead guitar, the late Bobby Lloyd Hicks sits in on drums and former Ozark Mountain Daredevils John Dillon and Supe Grande guest on mouth-bow and spoons respectively–lending that cute Ozark touch. The album was recorded at Nick Sibley’s studio in downtown Springfield and Sibley filled out the record by playing drums, bass, harmonica and keyboards. He hired trumpets, violins and cellos for finishing parts.

Around Springfield clubs and coffee houses, Waterworth is backed by her band NRA (Nick Sibley on guitar, Ruell Chappell on keyboards and Abbey), and NRA will headline the Springfield Jamboree at 8 p.m. June 1 at FitzGerald’s in Berwyn.

Donnie Thompson and Waterworth will open the evening with an acoustic set. “Rose Bridge” features covers of the Brenda Lee hit “I’m Sorry” (written by Springfield’s Ronnie Self), “The Letter,” (written by Springfield’s Wayne Carson), “Blue Kentucky Girl,” the Loretta Lynn-Emmylou Harris hit written by Springfield’s Johnny Mullins and even the pop-rock hit “Sugar Shack,” written by Keith McCormick, who had lived in Springfield since the early 1970s.

All those Springfield songwriters are dead.

“I wanted to know everything I could about where I came from and where this music came from,” Waterworth said during a conversation in Sibley’s spacious studio. “My interest in music history became an interest in art history and history of culture.”

I wanted to know if her college peer group is curious about her roots music interest.

“No,” she answered quickly. “I told someone last year I was studying history and might minor in Ozarks History and they were like, ‘Really, Ozarks History?’ That sounds like the nerdiest thing.’ But that’s what pumps my heart. Every time I talk about it, it fills me with joy. People in my age group aren’t really considering where they came from–yet. I’m not sure when that happens or why I have thought about that forever.

“Maybe it is because my family was from around here and I was never displaced like lots of people were when they were young. Oral tradition lasts three generations. A lot of music and culture is being lost because oral traditions are going away and people aren’t recording it. Especially in this area, there’s lots of untapped history. It’s still kind of a secluded region and it especially was 50, 60 years ago.”

“It is an area people don’t think about.”

The album is named “Rose Bridge” as a tribute to one of Si Siman’s publishing companies. Siman was a co-founder of the Ozark Jubilee concert series and ABC-TV show that in the mid-1950s was the first to broadcast country music across America–from the since-razed Jewell Theater in downtown Springfield.

“Rose Bridge” was named after Si’s wife Rosie and Wayne Carson’s wife Bridget.

Sibley said, “Abbey is only twenty, but has an encyclopedic knowledge of music of many genres and periods. She has an amazing voice. No auto-tune was used on this CD. She plays guitar, banjo and bass. She wanted to do her own interpretations of the varied types of songs that have come out of the Ozarks. Some were worldwide hits. Some are local favorites. And one is totally unknown–that would be mine.”

Sibley, a former member of the Springfield pop-rock-country-punk-surf band The Skeletons, wrote the novelty song “Cheesey Bread” for “Rose Bridge.” It’s just a few tracks ahead of the “Top Gun” Academy Award winning song “Take My Breath Away,” written by Springfield’s Tom Whitlock.

“Rose Bridge” is Waterworth’s second independent CD. Her 2015 acoustic self-titled debut includes Sibley originals, Elizabeth Cotten’s “Shake Sugaree (popularized by the Grateful Dead) and an honest cover of Bobbie Gentry’s “Ode to Billie Joe.”

NRA has been playing around Springfield since 2014. The Nick Sibley-Ruell Chappell partnership began in 1974 when they debuted at a Shakey’s Pizza Parlor in Springfield. Chappell is a Springfield native who was a mid-1970s member of the Ozark Mountain Daredevils and in 1989 was a cast member of the popular musical “Pump Boys and Dinettes.”

A native of El Dorado Springs, Mo., Sibley has been writing and producing jingles for companies across America out of his Springfield studio. Sibley built the studio out of the shell of a former warehouse and has owned and operated the space since 1981.

The Ozark Mountain Daredevils and Brewer and Shipley of “One Toke Over The Line” fame have recorded at Sibley’s studio and Brad Pitt did movie voice overs there. “He still owes me forty bucks,” Sibley cracked. “He was home for Christmas and he came to record on a Saturday morning. This was twenty years ago. He told me to send the tape to Miramax in New York and I never got paid. (Original ‘Newlywed Game’ host) Bob Eubanks did an ‘American Express’ commercial here.”

Sibley does spots for Lay’s Potato Chips, Bass Pro Shops and O’Reilly Auto Parts among others. Bass and O’Reilly are headquartered in Springfield. Ozark Mountain Daredevils Steve Cash and John Dillon laid down the original “O-O-O’Reilly” vocals, charging the company one dollar. “We do about 200 O’Reilly commercials every month here,” Sibley said. “I did the music 15 years ago. They come in and record in Spanish and English.” Sibley’s studio is just two blocks away from the late Lou Whitney’s studio.

Springfield’s music history is deeply rooted in NRA.

Chappell worked for Si Siman, playing on country records produced by Siman and Wayne Carson. NRA’s repertoire includes Sibley originals like “Albino Farm” (a true story about the 1930s albino Sheedy family that farmed at night outside of Springfield), the lite-country anthem “Life in the 417″ (Springfield’s area code) and the irresistible 2017 pop anthem “Bang-Bang Summer.”

Waterworth explained, “There’s something about these older songs that people made for the sake of making art. That’s what folk tradition is. People making this for the pleasure of sharing, That’s one reason I’m drawn to it. It wasn’t set up for commercialism. I had the pleasure of playing ‘Blue Kentucky Girl’ for Johnny Mullins’ wife and she was so happy that somebody was still interested in it.”

Waterworth works part time in Archives and Special Collections at Missouri State. She transfers old recordings into videos for the Gordon McCann Ozarks Music Collection.

McCann audio and video taped more than 3,000 hours of regional fiddle music, house parties and compiled 200 notebooks filled with lyrics and transcriptions of conversations. McCann, 86, is a Springfield native who spent his youth floating on johnboats on rivers in the Ozarks. “We’re putting his videos on YouTube so they’re accessible,” Waterworth said. “It’s Smithsonian level stuff.”

And of her essential “Rose Bridge” recording Waterworth explained, “I wanted to show people all of the beauty that comes from this area that we don’t think about. And maybe get people to discover more. You don’t have to go to St. Louis or a bigger city to hear good music. This area has made a lot of music. Whenever you play a good song and people realize it was written here, they’re surprised.

“They don’t think that kind of greatness can happen in their hometown.”

Abbey Waterworth is from Clever, Mo, in Christian County about 20 miles south of Springfield. The clever small town name reminded me my interview with the then-unknown Faith Hill, who was from Star, Miss.

“Not much goes on in Clever,” Waterworth said. “There’s a Murfin’s Market, the local grocery store and two gas stations. It was a farming community for a long time and now people are drawn to the school systems there.”

Waterworth attended Clever RV, a consolidation of five one-room school houses. “Yes, it sounds like something from a camping trip,” she said. “It adds to the ‘hillbilly value’ a little bit.”

Her mother Connie has been a successful stay at home mom. “My Dad (Bryan) has driven a truck as long as I can remember,” Waterworth said. “He hauled diesel fuel for Burlingt0n-Northern Santa Fe. Railroads were a big part of Springfield’s economy at one time.”

Her great grandparents were from St. Louis and moved to Competition, about two hours north of Springfield. Her great-grandmother played guitar until she had a family. Waterworth’s grandfather was a barber who bought a 1937 Gibson and learned how to play it for rural Friday night house parties. “They would go house to house every Friday night and play music,” she recalled. “Mostly bluegrass, but they’d play Ernest Tubb and old folk songs. He loved Jimmie Rodgers. I heard all that. My Dad learned guitar from listening to the Ozark Mountain Daredevils. Dad would get on his bicycle and ride down to the Nixa Trout Farm (in Nixa, Mo., outside of Springfield) where the Daredevils practiced. He would listen to their practices. My oldest brother learned how to play and then my second brother learned how to play. I was the last. So there really wasn’t an option.

“It was something I felt I had to do to be part of the family.”

Music filled the halls of the house in Clever and plenty of CDs were packed for family road trips. “I grew up on bluegrass but I love the Beach Boys and Rolling Stones,” she said. “I started singing when I was seven and started guitar when I was nine. Then I picked up banjo.”

Waterworth has been singing as long as she can remember. “My family needed a singer.” she said. “We had a guitar player, a bass player and a mandolin player. My brother told me I was singing melodies before I could talk. When I was growing up the Dillards were a influence. Some of them lived around here. As I got older, I got into John Hartford, who was from St. Louis and who played with the Dillards and then Gillian Welch–she was a huge influence. But there was a point where all I did was listen to music that I hadn’t heard before.”

Nick Sibley’s sense of a musical pop hook is in the rarefied air of Nick Lowe or Marshall Crenshaw. His playful approach to songs about cornbread and buried cats reminds me of Chicago’s Chris Ligon. Sibley’s hilarious true story about a Missouri undertaker, “Don’t Be Drinkin’ No Beer While Your’e Working on my Mama” has been recorded by Ray Stevens but has yet to be released.

“You write a song, open it up and then the song appears,” Sibley explained. “I come up with the germ of an idea and let it unfold. Look for rhymes. I feel I find a song more than I write.”

Sibley inherited an eye for detail from his mother Peggy Thatch Sibley while growing up in El Dorado Springs, an hour south of Springfield. His father was a grocer, his mother is a piano player and painter.

“She paints pictures of bridges and flowers and all kinds of stuff,” Sibley said. “You see her prints at Wal-Mart. I’ll go into a hotel room and find my Mom’s painting on the wall. Let’s say bird houses are big this year. She will do a series of bird houses. She paints photographs of those styles but she aspires to loosen up and be more expressive.

“I find myself writing the same way she paints. In order to fight that I’ll throw some more paint on the canvas. It’s contrived random. Do I rhyme where it should be or don’t do a rhyme? People who do it for real, that’s genius stuff. Me? I pretend to be a genius. I write jingles. That’s what I do.”

“About every three weeks, TV stations coast to coast, north to south fly me in. California to New Jersey. They bring their clients in every hour and a half. They tell me about their business for 30 minutes or so and I find some germ where I can write about something. They leave the room for 20 minutes and I write their jingle. A jingle is 30 seconds long. And you want to say something good about the client. They come in and I play it for them. If they like it, I come back here and produce it with real singers and stuff. Then the TV sends me a contract.

“ I’ve written thousands and thousands of jingles. The client takes it home. He says, ‘I know you’re an expert, but my daughter thinks it should sound more like this.’ You’re always pleasing the lowest common denominator, just like in popular music. That’s what you’re going for.”

Sibley’s approach is not unlike what hot pop (Taylor Swift, Lorde) songwriter Jack Antonoff told the New York Times earlier this week: “The heart and soul of pop is newness, excitement, innovation. The music business is built on chasing that ambulance–‘someone did it, let’s go that way.’ I don’t want to be a part of that. I want to be away from it.”

Antonoff should move to Springfield.

Sibley came to Springfield in 1971 to study marketing at Missouri State. “But Springfield bands would come to El Dorado Springs every Friday and Saturday night,” he said. “They were big stars to us. They knew all the right chords to the songs and I would be the guy standing by the PA watching them play That’s how I met Lloyd (Hicks, all-world drummer. He was the drummer for Lord Mack and the Checkmates. Supe (Michael Granda of the Ozark Mountain Daredevils) came to my town.

“The first studio in Springfield was started by Si Siman in 1968. It was called Top Talent. That’s where Wayne Carson (The Box Tops, Gary Stewart, etc.) did his demos and it became kind of a party place. Then Si said, ‘I’m outta here.’ He told me when I was going to build this place, ‘You’re going to regret it.’ Because I’d be using musicians (laughs). About 1972 Si sold his studio to a group of investors whose core group was local preachers. They made a gospel studio out of it. They’d do an album a day on Saturdays and Sundays. I knew everybody who played in every band in town.

“For me, Springfield music was like collecting baseball cards.”