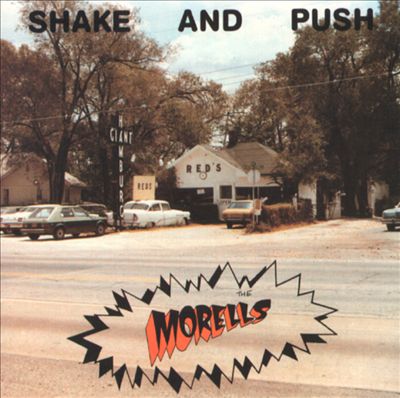

RIP David Leong, founder of “Springfield Style Cashew Chicken”

“The Cashew Chicken Capital of America” is a true made-in-America story delivered from the hills and highways of Springfield, Mo.

Springfield’s population is approximately 168,000 people. And nearly 100 regional restaurants serve cashew chicken.

David Leong, the beloved founder of “Springfield Style Cashew Chicken” died July 20 in Springfield. He had been battling pneumonia. David was 99 years old. He would have turned 100 on August 18.

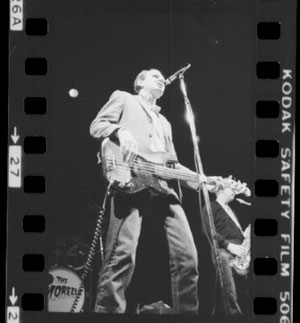

David’s remarkable journey incorporates so many things I love: cashew chicken, Route 66, soul music, immigrant dreams, supper clubs, and the late Springfield musician and avatar of good, Lou Whitney.

David moved to Springfield from Pensacola, Fla. in 1955. Prominent Springfield neurosurgeon Dr. John Tsang was vacationing in Pensacola and became a fan of David’s cooking. Tsang told David he could make more money in “The Queen City of the Ozarks.” David could not even locate Missouri on a map.

By the early 1960s David was a chef at the now-defunct Grove Supper Club on Old Route 66, which slices through Springfield. The Grove was a cool place, with low ceilings and comfy booths embedded with flamingo prints.

In a 2001 conversation at his now-defunct Studio in downtown Springfield, Whitney told me how he saw the Drifters perform at the Grove. “It had gone through a series of owners and the last burning had been investigated for arson, although nobody was arrested.

“By virtue of David Leong’s Asian heritage, he had a few Asian dishes on the menu. You could get pepper steak, some kind of fried rice.

“And cashew chicken.”

David conjured up his own style of cashew chicken. He cut the chicken into small nuggets, dipped them in batter and spun them through a deep fry. That gave the cashew chicken a fried chicken flavor. David then covered the chicken with Chinese oyster sauce, and over that, he sprinkled chives and/or chopped scallions. Salted cashews were applied as the finishing touch.

In 1998 David told the Associated Press, “Everywhere I looked, restaurants were serving fried chicken, fried chicken, fried chicken. So I made American fried chicken with Chinese gravy.”

One evening during the early 1960s a semi truck plowed off Route 66 into the kitchen of the supper club. To demonstrate what happened, Whitney stood up from behind a desk in his studio and threw himself against a wall. Hard. Like ice hockey check hard.

I had to ask Whitney if he was okay.

He was and he continued, “David was pinned against the wall and suffered minor injuries. He ultimately got a settlement.”’

David took insurance money and in 1963 opened his own restaurant – Leong’s Tea Room – on the then-unsettled far south side of Springfield. “That was Springfield’s first Asian restaurant,” said Whitney, who moved to Springfield in 1970. “Of course, he took his cashew chicken recipe out there. And people started flocking to Leong’s.”

Fayetteville, Ark., is about 130 miles from Springfield. At the end of the Vietnam War, Fort Chaffee near Fayetteville was the nation’s largest Vietnamese refugee center (50,797) and the last to close (Dec. 20, 1975).

Area dioceses helped with the resettlement of the mostly Catholic Southeast Asian refugees. Many refugees settled in Springfield.

Guess what business they got into?

“It was BOOM!” Whitney said as he finally returned to his chair. “All of these carry-out Asian places started opening up. Every place had the cashew chicken. The people in Springfield were conditioned to cashew chicken. These Asian families came here, looked around and went, ‘We can buy a nice house in the Southern Hills. Have Trans-Am cars, nice clothes. And all we have to do is work? Not a problem!’ Now, you go to Dallas, Texas or Kansas City, Mo. and see – ‘Cashew Chicken: Springfield Style.’ ”

So it was probably around the time of this memorable 2001 conversation with Lou Whitney I started thinking maybe I should do more than just write about Springfield music. Over the next few years, Whitney and I began talking about things like long-form stories on the history of Springfield music and maybe a documentary.

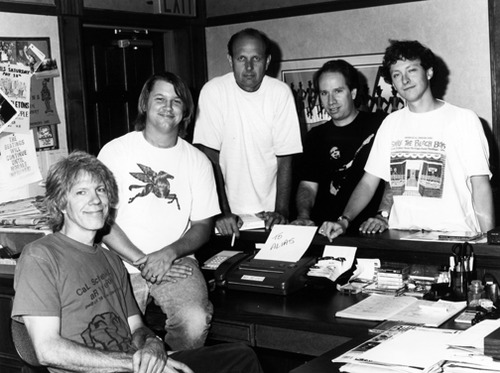

Reeling in friends like Chicago producer Jamie Ceaser, my former Chicago Sun-Times colleague, and videographer Jon Sall and my cameraman friend Tom Vlodek, we began work on “The Center of Nowhere” documentary in 2013. We had no money but we ate a lot of “Springfield Style Cashew Chicken.” I remained obsessed with all the angles of David Leong’s story. It was so much more than a plate of cashew chicken.

Springfield songwriter Nick Sibley was gracious enough to compose “The Cashew Chicken Song” for our documentary, with sweet lead vocals from Springfield’s Abbey Waterworth. Chicago’s Sharon Rutledge provided excellent cashew chicken animation. More than once I dragged my crew and friends to Leong’s.

They thought I was nuts. Some of them still do.

We interviewed David, his son Wing Yee and Whitney at Leong’s Asian Diner, 1540 W. Republic Rd. on the southwest side of Springfield not long before Lou’s death in October 2014. Wing Yee is the Leong’s executive chef and he ran the business with his father and two brothers, who share the first names of Wing (which means “prosperous” in Cantonese,)

Bits of Lou, David, and Wing Yee are in “The Center of Nowhere” documentary, but I had to come to the harsh reality that 20 minutes of the documentary could not be devoted to “Springfield Style Cashew Chicken.”

These are some of the things I learned during that afternoon that are not in the doc (Maybe they will be in the DVD extra!)

David was born in Canton, China (now Guangzhou.) He came to America in 1940 at the age of 20. He became a U.S. citizen because his father had already settled in America.

“It was the wrong time to be twenty and become a U.S. citizen,” David said with translation help from Wing Yee. “I was immediately drafted into the United States Army. I was on the fourth wave of Omaha Beach in Normandy.

“I jumped off the (amphibious) Higgins boat when it was coming on shore. That saved my life. By going off the edge instead of going down the ramp. Because when the ramps opened the Germans would open up (fire) on the boats. The water was over my head. So I had to learn to swim fast.” David also prepared meals in his spare time and his Army comrades often said they were the best-fed troops in Europe.

When David arrived in Springfield in 1955 he first partnered up with his friend Dr. Tsang. Wing Yee said they opened the Lotus Garden restaurant together. “Dr. Tsang wasn’t a very good business person,” Wing Yee added. “He’d invite all his doctor friends and not charge them. From there, my dad went to the Grove Supper Club, which at the time was a very prominent place to work.”

Si Siman, the legendary Springfield music producer, songwriter, and co-founder of the “Ozark Jubilee” television show would bring friends such as Chet Atkins, Johnny Cash, and Red Foley to the Grove. At the time that David worked at the Grove, it was the only restaurant in Springfield where customers could dine and dance. It was a fancy supper club where women wore pearls and cocktail dresses and men wore suits.

In 1969 a McDonald’s research and development team visited David at the original Leong’s Tea House.

“They wanted to watch the process of how we cut the chicken, bone it, breaded it and fried it, how we used sauces.” Wing Yee said. “After three days they asked for my dad’s recipe. My dad said, ‘Unless you pay for it, I’m not going to give them to you.’ We thought nothing more of it but later (1983) McDonald’s corporation comes up with a Chicken McNugget. I like to think we had something to do with that.”

The Leongs are pioneers in Ozarks cuisine and culture. Wing Yee was born in 1956 in Springfield. “Our family was the first Asian family in Springfield and some people looked at us like, ‘Who are these aliens?’,” he said in 2014. “When we started we heard everything about we’re serving cat, all kinds of things that were never true.

“The plus side was that my dad introduced home cooking, quality service and developed friendships that last to this day. There was always the biased people, the negative people you didn’t want to be around, but the good people, the ones that counted the most, they would help my dad out. He had a lot of good friends.

“And they were friends for life.”